By Conner Tighe

The following article is on a posting schedule, making some dates mentioned upcoming.

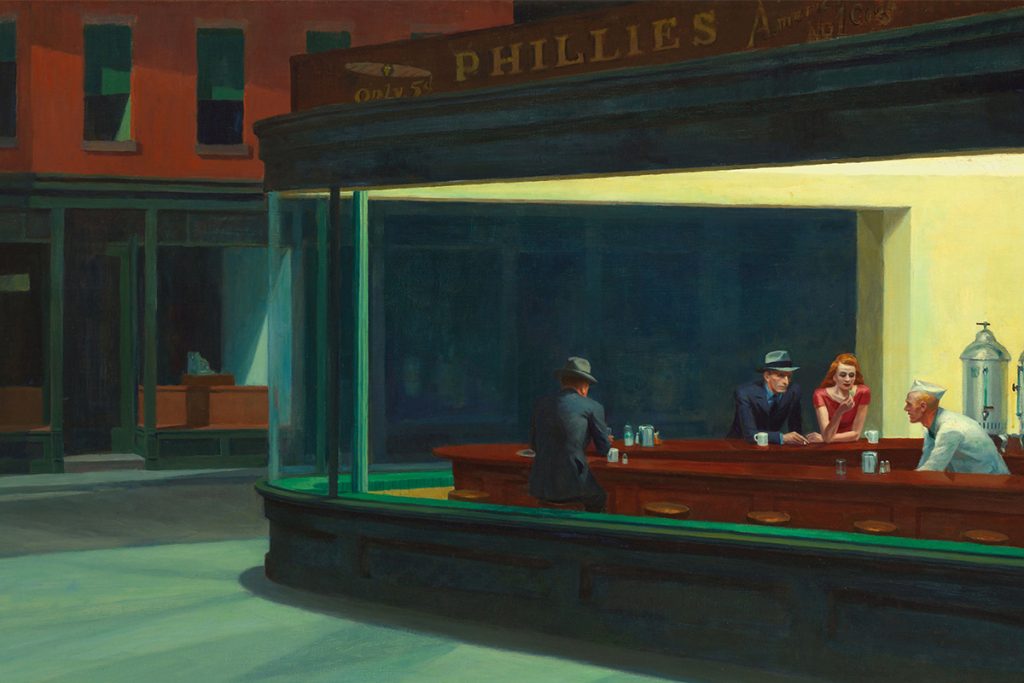

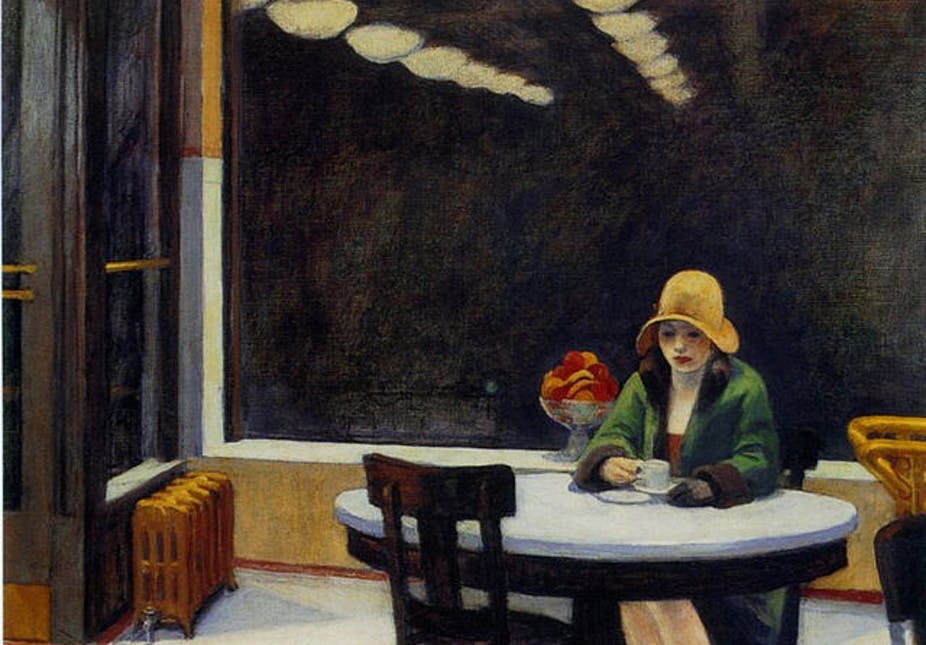

In celebration of Edward Hopper’s 139th birthday today, we’ve highlighted one of the greatest American painters, Edward Hopper. Hopper’s work captured the eerie, dark corners of America. He took the busiest, most bustling areas in America — bars, dance clubs, restaurants — and put his own spin on the location. Although he has captured various scenes of artist angst, one, in particular, raises valid discussion for one or possibly his greatest work ever, Nighthawks.

The story behind the painting:

The painting appears simple; four figures — a late-night worker, a couple, and a gentleman seated off by himself. The scene is timeless and as one might notice, there are no visible exits from the diner area, making it appear as if everyone is stuck forever in the glass wall. The scene was inspired by a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue where two streets intersect, as shown in the painting. New York has the highest population density rate in America, yet here there’s nobody but the figures inside the diner. Some believe that the “lady in red” was inspired by Hopper’s wife, Jo. He denied these claims and the fact he was purposely capturing the loneliness of American life.

Capturing loneliness:

Unfortunately, Hopper is no longer around for questioning on one of his greatest masterpieces, but some theories may be raised to explain the loneliness that’s captured here. The painting was created in 1942, the “beginning” of World War II and a year after America entered the war. Most of the demographic that would’ve been on the streets at night were drafted and America consisted mainly of a hardworking class of women.

An eerie glow:

Hopper knew how to capture loneliness merely with the strokes of the brush when he was painting Nighthawks. Fluorescent lighting was relatively new in the 1940s, inspiring Hopper to capture shadows and semi-lit areas. Low-key lighting is commonly used in horror films for its fear-factoring effect, like John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Less lighting creates more mystery, more room for imagination, and more room for fear.

Sources: Art Institute of Chicago, NYC Department of City Planning, Google Arts and Culture, Office of the Historian, Austin School of Film

Images: The Conversation, Bloody Disgusting

Featured Image: Artsy